Managing the numbers and availability of laboratory animals is an ongoing challenge in animal research. Our research seeks to understand why.

The life science industry sells a wide range of products and services including making bespoke and generic animal models. Biotechnologies enable the faster and more efficient creation of animal models, but with it animals that can’t be sold are bred or used as surrogate mothers, in the process.

Commonly, a request for a mouse model to be made requires the lives of other mice to be made; many of these will not be suitable for a research experiment.

Researchers try to ensure the timely availability of laboratory animals while minimising surplus, to meet animal welfare and production efficiency goals. Some laboratories house ‘tick over’ colonies. These are groups of animals that are kept alive on the shelf and that produce litters of young, so should a request for some of this type of animal come through then there are some available.

Researchers are increasingly encouraged to cryopreserve colonies. This means to freeze at very low temperatures embryos and gametes taken from mice in the colony, and to keep them in that state until they are unfrozen to be used in a surrogate mouse to ‘resurrect’ the colony back into living form when needed. They also are encouraged to maximise the value of their work by storing and sharing tissues and/or embryos, from the mice they use and kill.

Consequently, new materials (frozen embryos and animal tissues) and markets (paying for services that make bespoke animal models) are shaping the production, accumulation and circulation of research animals.

Research animals are embedded in broader economies of science. We study how its logics and practices conceive animals as resources yielding social and economic value, and how this influences their care in the laboratory.

Our research looks beyond the moment of the experiment to encompass the whole life cycle of laboratory mice, from breeding to tissue biobanking. This is important because it broadens our attention to the experience of laboratory animals throughout their life, and also towards those animals who are involved in research, but never undergo experiments themselves: they may instead be used for breeding more animals, as ‘sentinels’ for colony health, as sources of tissue for research, or simply be surplus to requirements. By focusing our research on these animals, we can shed new light on the social relations that underpin animal research in the UK – through regulation, ethical principles and tools, and interpersonal relationships. These social relations are the main object of study of the Animal Research Nexus project.

To do this, we have been carrying out qualitative research into the breeding, supply chains, and biobanking of laboratory mice. It involves using methods and tools from the social sciences to understand the perspectives and experiences of people who are involved in animal research and reproduction in a variety of ways.

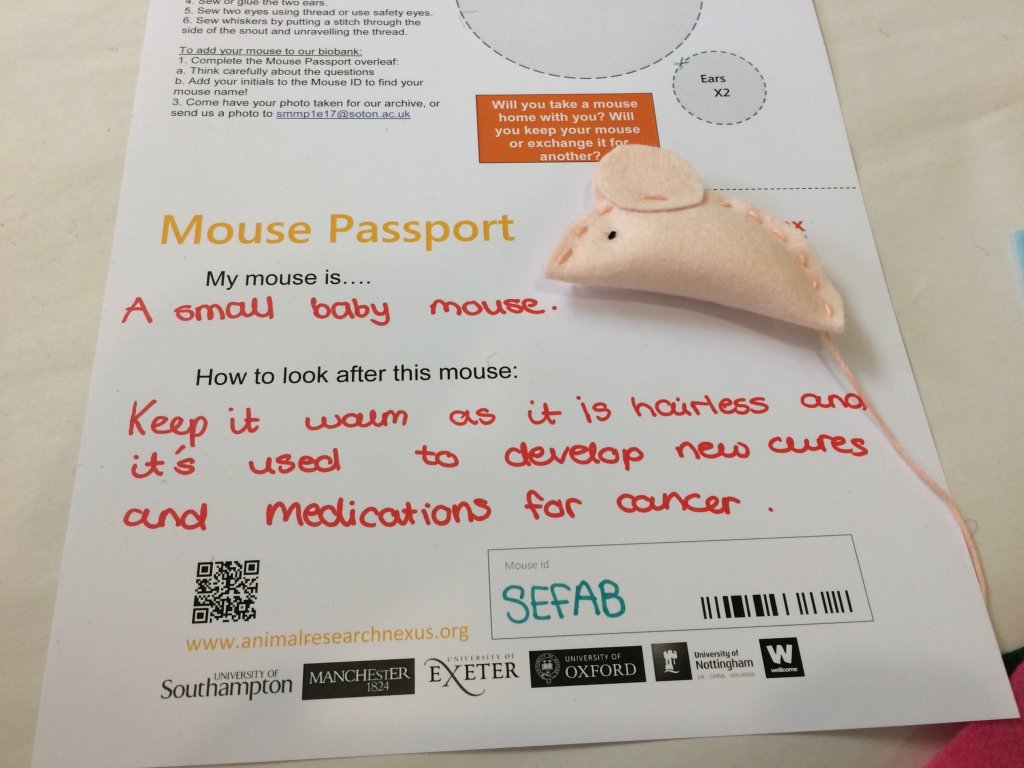

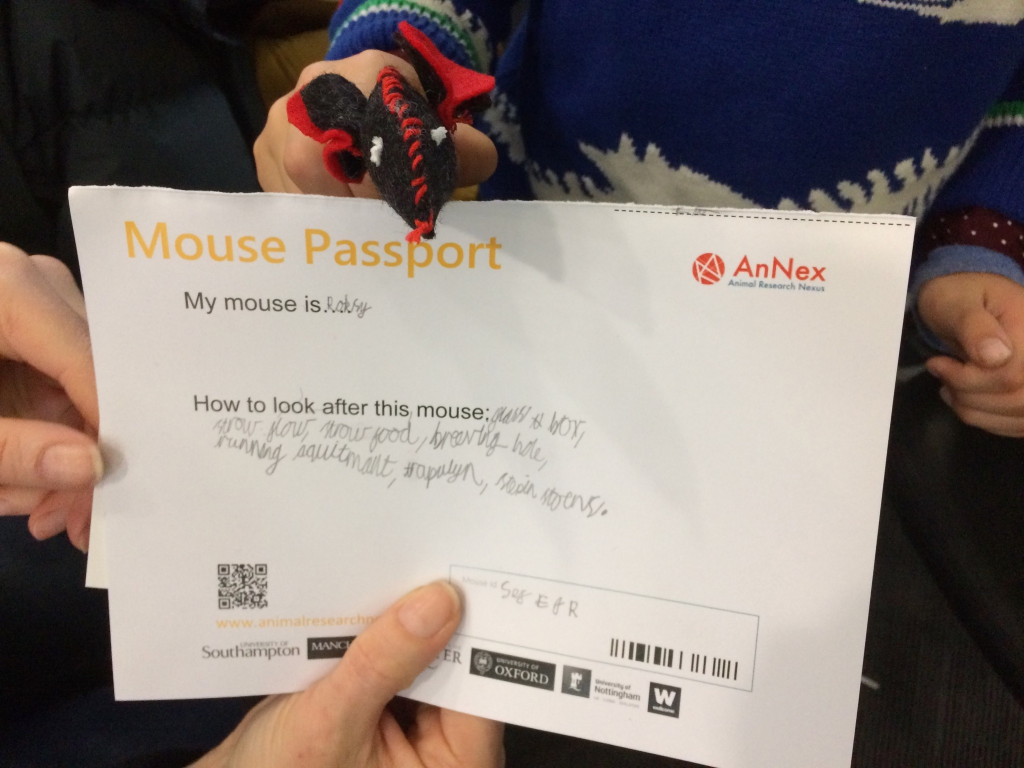

From December 2017, we have been carrying out interviews and shadowing people as they go about their work in animal research, either caring for animals (animal technicians, veterinarians) or doing scientific research or projects involving animals (as experimenters, or scientists working in biobanks). At the same time, we began developing the Mouse Exchange as a means to talk about our research with the public.

0 Comments